The European Union’s CO₂ quota system was once hailed as a bold, market-based solution to drive decarbonisation across the automotive industry. It promised innovation through incentives: those who polluted less would be rewarded, while those lagging behind would pay for their inaction.

Yet, five years into its full enforcement, the results are far more nuanced. The regulation has reduced average fleet emissions, but it has also exposed a deep paradox: a system that allows companies to “buy time” instead of progress, and one that unintentionally strengthens competitors financed by European money.

This article explores the economic and environmental drawbacks, the built-in advantage of “green frontrunners”, the reasons behind the EU’s slow green transition, and why 2025 marks a turning point for both policymakers and the automotive industry.

Economic and Environmental Drawbacks

Economic perspective

The new regulation requires that by 2025, the average CO₂ emissions of new passenger cars must be 15% lower than 2021 levels, which means a fleet-wide target of roughly 95 g CO₂/km. Publications Office of the EU, theicct.org

Manufacturers who fail to meet the target face fines of up to €95/g/vehicle over the limit. Financial Times

As a result, carmakers particularly those who have not yet shifted to electric production increasingly prefer to comply through quota purchases (buying CO₂ credits from cleaner manufacturers) rather than investing in their own technological transformation.

For example, EU-based carmakers plan to form pools in 2025 to trade CO₂ credits collectively.

According to one European Parliament statement, the European automotive industry is “indirectly financing” competitors that produce only electric vehicles and sell their surplus credits. European Parliament

Thus, the economic disadvantage becomes evident: traditional manufacturers face heavy costs (technology investments, penalties, credit purchases), while their rivals, mostly EV specialists, gain a relative advantage.

An additional economic risk lies in regulatory uncertainty: for instance, the EU allows a three-year average (2025-2027) for compliance, reducing short-term innovation pressure. Climate Action

Environmental perspective

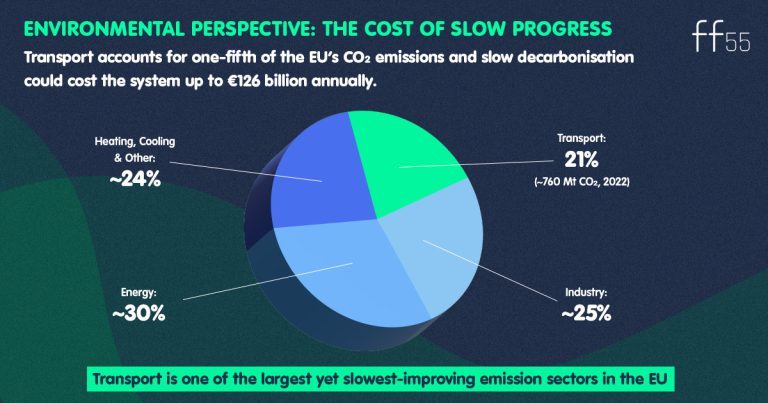

Although the average emissions of new vehicles in the EU have declined, progress has been slower and less straight forward than intended. A 2025 study estimated that road transport produced around 760 million tonnes of CO₂ in 2022, accounting for roughly 21% of total EU emissions. arXiv

Critics argue that the ability for “under-the-cap” manufacturers to sell their surplus credits weakens the incentive for every producer to make real reductions.

In practice, a manufacturer can fall behind, buy credits, survive financially and delay technological advancement. Transport & Environment

This delayed progress shifts the burden onto other sectors such as industry and heating, since the remaining carbon budget becomes tighter. The cited study warns that if road transport decarbonisation continues slowly, system-wide costs could rise by €126 billion annually. arXiv

The advantage built on European money

From the quota trading system, “green frontrunners” typically electric vehicle manufacturers have earned substantial revenue. By selling credits, they gain a competitive edge while traditional manufacturers must pay them.

This creates what could be called the “advantage built on European money”: EU legislation aims to promote domestic decarbonisation, yet in practice, those already ahead profit often at the expense of their slower peers. According to the European Parliament, most credits are generated by electric vehicle producers, meaning European automakers are effectively providing income to their own competitors.

This dynamic also weakens Europe’s global competitiveness: if part of the automotive profit stream flows to non-European players through credit trading, local manufacturers face both a technological and financial disadvantage.

As one parliamentary report bluntly noted:

“Europe’s car industry is indirectly funding its own competitors.”

Those ahead mainly EV-focused firms can reinvest their credit income into further innovation, widening the gap even more. In economic terms, the system creates a structural market distortion.

Why is the EU’s green transition so slow?

The reasons behind the slow progress are multifaceted:

- High transition costs:

The shift to electric vehicles demands major investment in battery production, manufacturing capacity, and charging infrastructure, a challenge both financially and operationally. Electrada - Regulatory flexibility and uncertainty:

Under Regulation (EU) 2019/631, automakers must cut fleet emissions by 15% by 2025.

However, the EU has proposed allowing three-year averaging (2025-2027) for compliance, which dilutes the urgency of action (European Commission). - Market and consumer factors:

If consumers continue choosing internal combustion vehicles due to high EV prices or insufficient charging infrastructure, manufacturers have little incentive to accelerate change. - Quota trading as a safety net:

When buying credits is cheaper than reducing one’s own emissions, the innovation drive weakens the system and effectively offers a “back door” for delay. ReSearchGate

Finally, infrastructure and supply chain challenges such as access to critical raw materials for batteries or workforce reskilling are hard to scale quickly across the EU.

A turning point for the EU and the automotive industry

Between the 2025 target (-15%) and the 2030 target (-55% vs. 2021) lies a critical window of transformation. This period will determine whether the EU can meet its 2035 zero-emission new vehicle goal.

Two paths are now visible:

- Accelerated technological transition:

Rapid scaling of EV production, infrastructure, and battery supply with genuine emissions reduction instead of credit purchases. - Delay through quota trading:

A short-term escape that avoids fines but risks long-term technological stagnation and higher future costs (e.g., stranded combustion-engine assets).

EU policymakers also face a choice: whether to tighten or ease compliance rules. The recent proposal to permit three-year averaging signals flexibility, but critics warn it weakens the pressure to decarbonise.

Debates and emerging proposals

Across the European policy landscape, a wide range of potential solutions and reform ideas have been discussed to accelerate the transition of the transport sector. Analysts, NGOs, and institutions often agree on the urgency of change yet differ on how to balance regulatory pressure, industrial competitiveness, and consumer realities.

Some proposals circulating in expert and policy circles include:

Tightening or simplifying regulation:

- Several policy groups suggest reducing regulatory flexibility, such as the three-year averaging mechanism introduced for the 2025-2027 period, in order to maintain stronger innovation pressure. European Court

Revising the credit trading system:

- Think tanks like the ICCT argue that capping the share of purchased credits or improving transparency could limit “paper compliance” and better link revenues to real technological progress.

Encouraging investment and infrastructure development:

- Other sources highlight the need for stable incentives for electric vehicle and battery production, as well as faster expansion of the EU-wide charging network. European Commission

Conclusion

The debate over how to steer Europe’s transport decarbonisation remains wide open.

While some advocate for stricter regulation to guarantee real emission reductions, others caution that excessive rigidity could threaten the competitiveness of Europe’s automotive industry, a sector that still employs millions and underpins much of the continent’s industrial base. The CO₂ quota and credit system, originally designed to stimulate innovation, now exposes the paradoxes of transition: it enables compliance without necessarily driving transformation. For some manufacturers, it offers short-term relief; for the system as a whole, it risks long-term stagnation if not paired with deeper technological change.

The coming decade framed by the 2025 and 2030 milestones will therefore be decisive. With many reform ideas on the table but no single consensus, the challenge for policymakers and industry leaders is to find a balance between environmental ambition and economic realism.

If Europe succeeds in aligning regulation, investment, and consumer action, this paradox can still become an opportunity one that leads not only to a cleaner, but also a more resilient and competitive automotive industry.