In recent years, the European Union has embarked not only on the path toward an energy transition, but also toward energy independence. Following the sharp decline in dependence on Russian gas, a new era has begun: the rise of renewable energy sources is no longer merely an environmental issue, it has become an economic and geopolitical strategy.

But what does independence actually mean in practice? Which countries are leading the way, which EU programs are accelerating the transition, and what challenges still slow progress?

This article, in the spirit of the Fit for 55 (FF55) objectives, explores how Europe can become not only greener but stronger and more self-sufficient.

The rise of renewables in EU member states: Who’s leading?

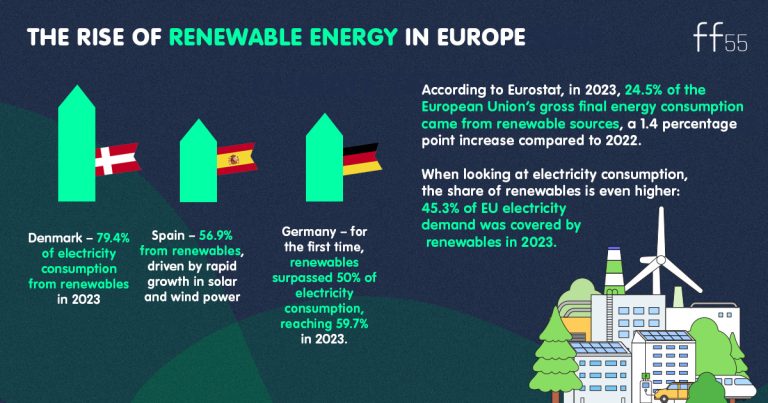

According to Eurostat, in 2023, 24.5% of the European Union’s gross final energy consumption came from renewable sources, a 1.4 percentage point increase compared to 2022. Eurostat

When looking at electricity consumption, the share of renewables is even higher: 45.3% of EU electricity demand was covered by renewables in 2023. Eurostat

Country highlights:

- Denmark – 79.4% of electricity consumption from renewables in 2023.

- Spain – 56.9% from renewables, driven by rapid growth in solar and wind power.

- Germany – for the first time, renewables surpassed 50% of electricity consumption, reaching 59.7% in 2023. Fraunhofer ISE, Eurostat

These figures highlight that some EU countries are well ahead of the European average in integrating renewables. On a practical level, this means a reduced share of imported fossil fuels and greater reliance on domestic green energy to meet demand.

EU programs accelerating the transition

REPowerEU – The energy independence initiative

The REPowerEU plan is an ambitious strategy launched by the EU to reduce its dependency on external fossil fuel suppliers, especially Russia and accelerate the green transition.

According to the plan, by 2030, solar capacity in Europe should reach 592 GW and wind capacity 510 GW. IEA, European Commission

Net-Zero Industry Act: Building green industrial sovereignty

Adopted in 2024, the Net-Zero Industry Act sets the target that by 2030, the EU should be able to produce at least 40% of its annual demand for “net-zero” (near-zero emission) technologies domestically. Eur-Lex

Together, these initiatives show that the EU is pursuing not only climate and energy goals, but also geostrategic independence, seeking a stronger, more autonomous Europe through the green transition.

The obstacles: What slows project implementation?

While the goals are clear and the direction strong, the practical implementation of the green transition is far from smooth. Several structural barriers still slow down progress.

- Permitting processes: slow approvals hamper momentum

One of the main challenges is the lengthy permitting process. In many EU countries, the approval of a new wind or solar project can take 3-5 years, involving complex environmental and spatial planning procedures.

According to WindEurope’s 2023 report, “permitting remains the single biggest bottleneck” for wind development in Europe, with about one-third of new projects delayed. Business Europe, WindEurope

The European Commission has recognized this issue, simplifying permitting is a core element of the REPowerEU plan, which encourages the designation of “renewable acceleration areas” where faster approval procedures apply. European Commission

- Grid capacity and network development: infrastructure falling behind

The growing share of renewables requires significant investment in electricity networks. Integrating new wind and solar installations demands not only new transmission lines, but also smart grids and energy storage systems.

According to the IEA’s 2024 Grid Integration Report, the EU will need to invest at least €400 billion by 2030 to modernize its power grid. Otherwise, 25-30% of renewable capacity could remain underutilized due to “grid bottlenecks.” IEA, Executive summary

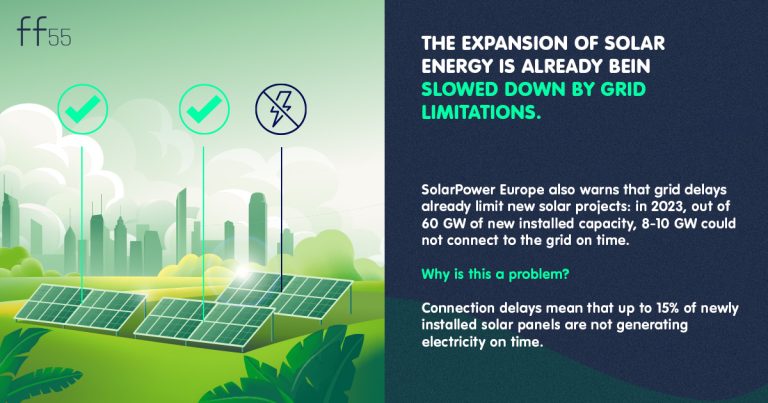

SolarPower Europe also warns that grid delays already limit new solar projects: in 2023, out of 60 GW of new installed capacity, 8-10 GW could not connect to the grid on time. SolarPower

- Supply chains and manufacturing: Green technology still import-dependent

One paradox of the green transition is that while the EU is reducing fossil fuel imports, a new kind of dependency has emerged on imported renewable technologies.

For instance, the solar PV supply chain is over 80% dependent on Asia, primarily China. This creates exposure to price volatility, shipping delays, and geopolitical risks. IEA

The EU’s response is the Net-Zero Industry Act, aiming for at least 40% of key climate technology manufacturing capacity, including solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, heat pumps, and green hydrogen electrolyzers to be located within the EU. European Commission

However, these investments face workforce, raw material, and logistics challenges. According to Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI), the growth of Europe’s green industry can only succeed if the EU simultaneously strengthens skills development and raw material supply chains. GTAI

Independence 2.0: Beyond the fossil world

In the 2020s, energy independence means far more than it once did.

Whereas the focus used to be on reducing reliance on external fossil supplies, mainly Russian gas and oil, today independence encompasses a broader strategy of green, technological, and industrial sovereignty that spans energy production, manufacturing, and employment.

- Energy independence: Powering from within

EU countries are steadily cutting fossil imports: in 2021, around 45% of EU gas consumption came from Russia; by 2024, that share had dropped below 10%. European Council

With the expansion of solar and wind generation, more energy now comes from domestic sources, reducing price volatility and ensuring more stable supply.

By 2024, Europe added over 60 GW of new solar capacity and 25 GW of new wind capacity, both record highs. European Commission

- Technological independence: Producing, not just consuming

True independence cannot rely solely on generating green energy. If the key technologies, solar panels, batteries, turbines, inverters are still imported, dependency merely changes form. That’s why the Net-Zero Industry Act sets the goal of producing 40% of strategic climate technologies within Europe by 2030. European Commission

This is not just industrial policy, it’s strategic security. A Europe that manufactures its own key technologies will free itself from both fossil and technological dependencies.

- Economic independence: A new growth model

Renewable energy and its related industries are creating hundreds of thousands of jobs across Europe. According to SolarPower Europe, in 2024 more than 650,000 people will be employed directly or indirectly in the solar sector, more than double the number in 2020. European Commission

This trend also opens up new industrial and export opportunities. Global demand for European green technologies, hydrogen, storage systems, and heat pumps is growing rapidly. Economic independence thus means Europe is becoming not only a consumer, but also a producer and exporter of clean energy.

- Social independence: Community energy and local control

Decentralized energy generation, such as energy communities, household solar, and local microgrids allows citizens to become active players in the energy market. As a result, independence is achieved not only nationally but also socially: energy becomes less centralized, revenues stay local, and people become true participants in the green transition. ScienceDirect

Conclusion

In practice, independence means that EU countries such as Germany, Spain, and Denmark are advancing not only in climate and energy terms, but also in geopolitical and industrial autonomy. Through the REPowerEU and Net-Zero Industry Act, the EU has created frameworks that enable faster transition and reduced dependencies.

However, challenges in permitting, grid capacity, and supply chains serve as a reminder: achieving these goals requires not only political will, but also effective implementation and continuous investment.